Deep Vein Thrombosis

Blood clots are lifesavers when they seal a cut. They can be dangerous, even deadly, when they form inside an artery or vein. Deep vein thrombosis (sometimes called DVT) is the formation of a blood clot in a large leg vein. It can also occur in an arm vein. Deep vein thrombosis can lead to a pulmonary embolism, or sometimes a stroke.

Blood that circulates to the legs and feet must flow against gravity on its journey back to the heart. The trip is aided by the contraction of leg muscles during walking or fidgeting. The contractions squeeze veins, pushing blood through them. Small flaps, or valves, inside the veins keep blood flowing in the direction of the heart.

Anything that slows blood flow through the arms and legs can set the stage for a blood clot to form. This can range from having an arm or leg immobilized in a cast to prolonged sitting or being confined to bed. Things that make blood more likely to clot, such as genetic disorders and cancer, are other triggers for deep-vein thrombosis.

Symptoms of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

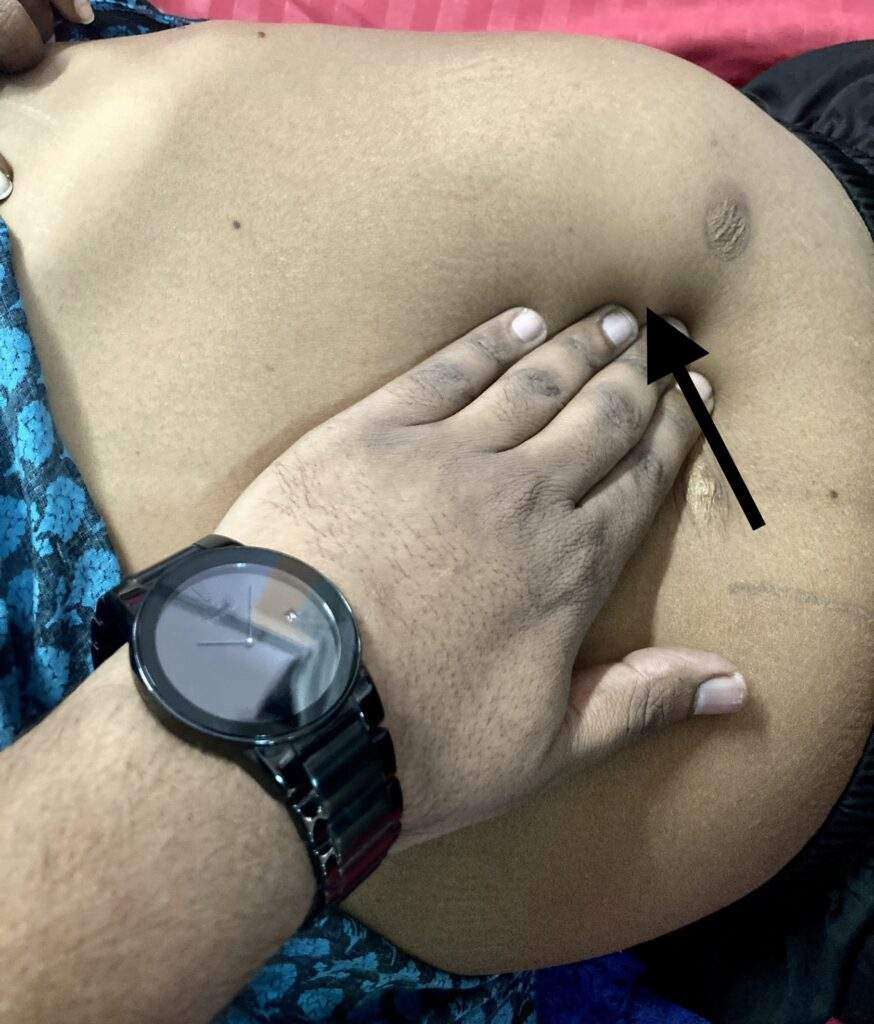

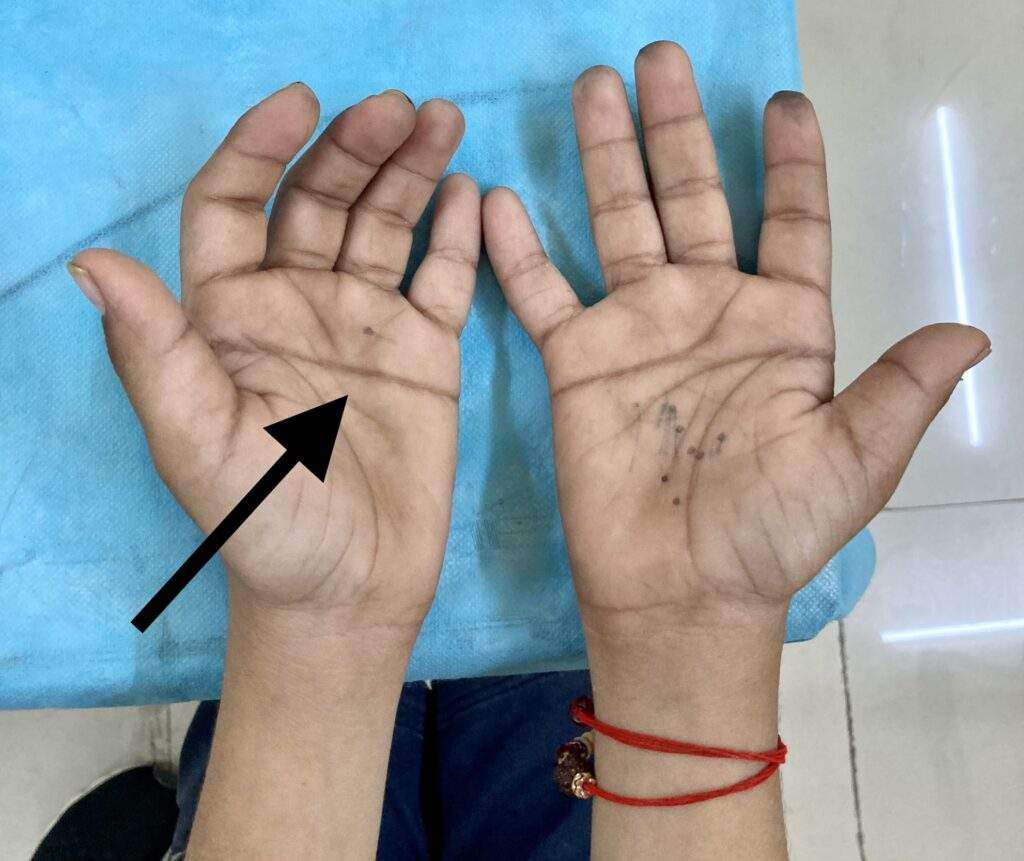

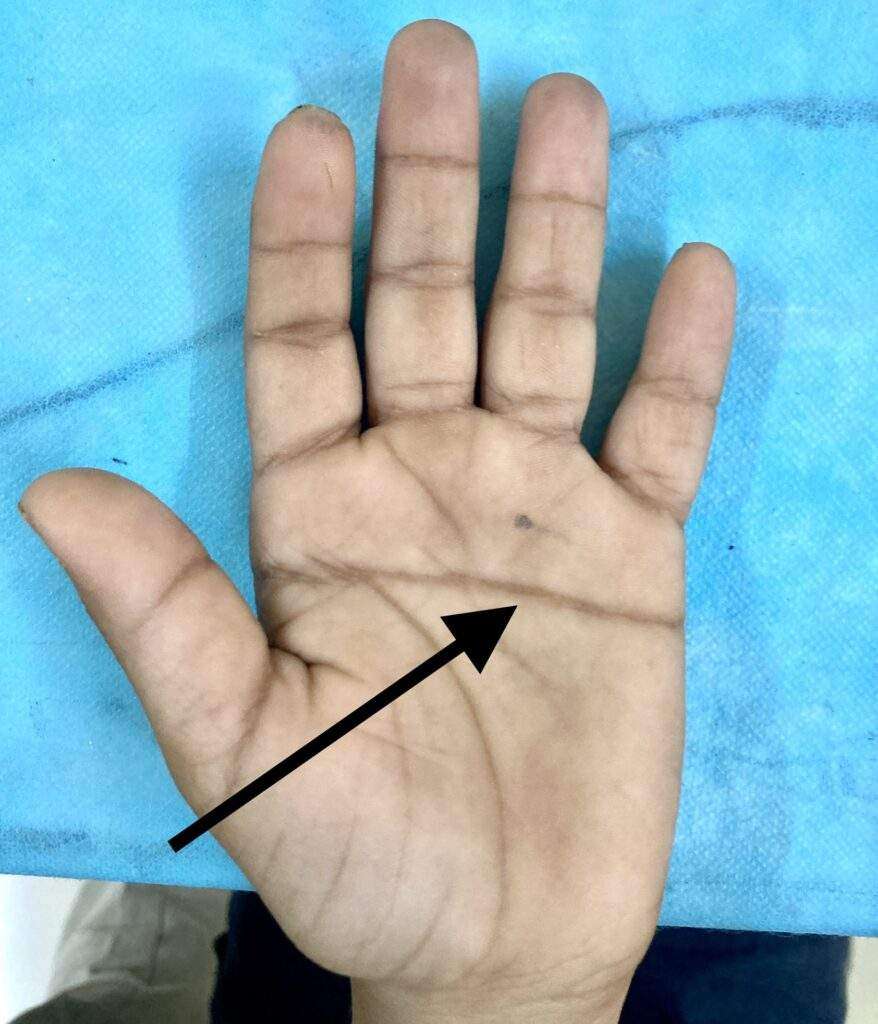

Deep vein thrombosis can develop silently. It can also cause:

- pain or tenderness in a leg or arm that gets worse with time, not better

- swelling in one leg or arm

- a reddish or bluish tinge to the skin of one leg or arm

- a leg or arm that feels warm to the touch.

The symptoms of pulmonary embolism include:

- difficulty breathing

- chest pain or discomfort that worsens with a deep breath or cough

- coughing up blood

- a fast heart rate

- sudden lightheadedness or fainting

Diagnosing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

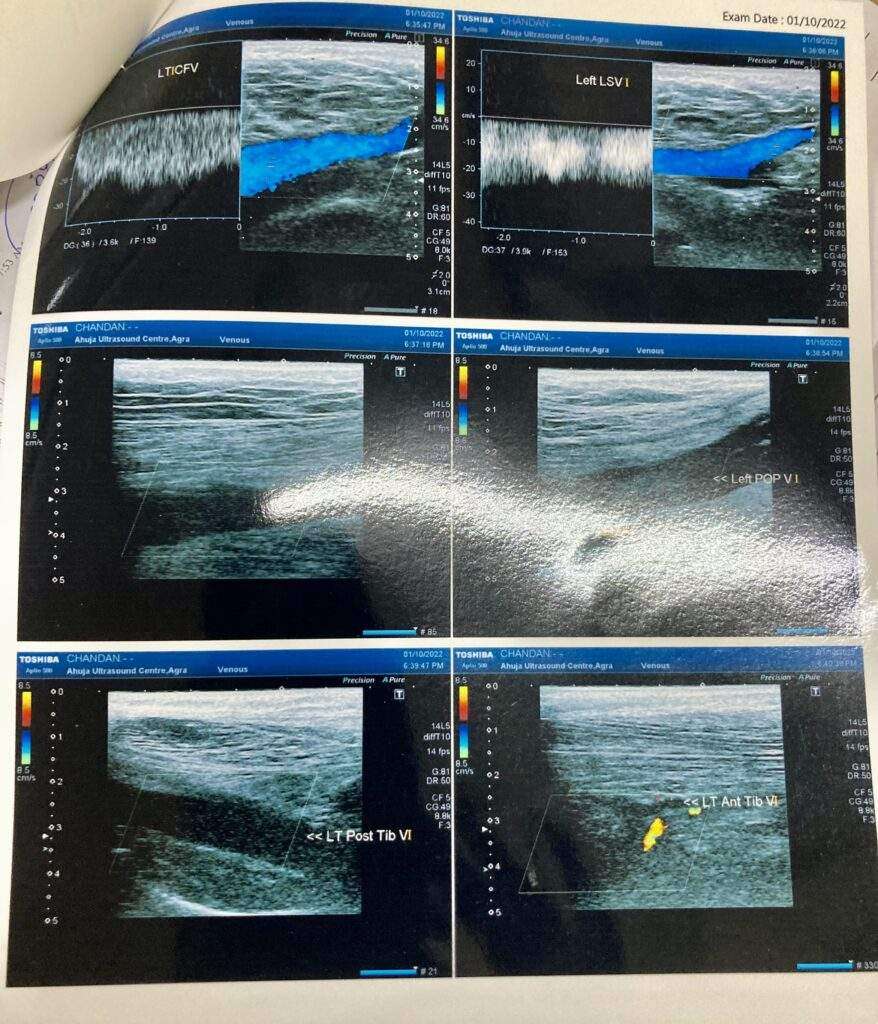

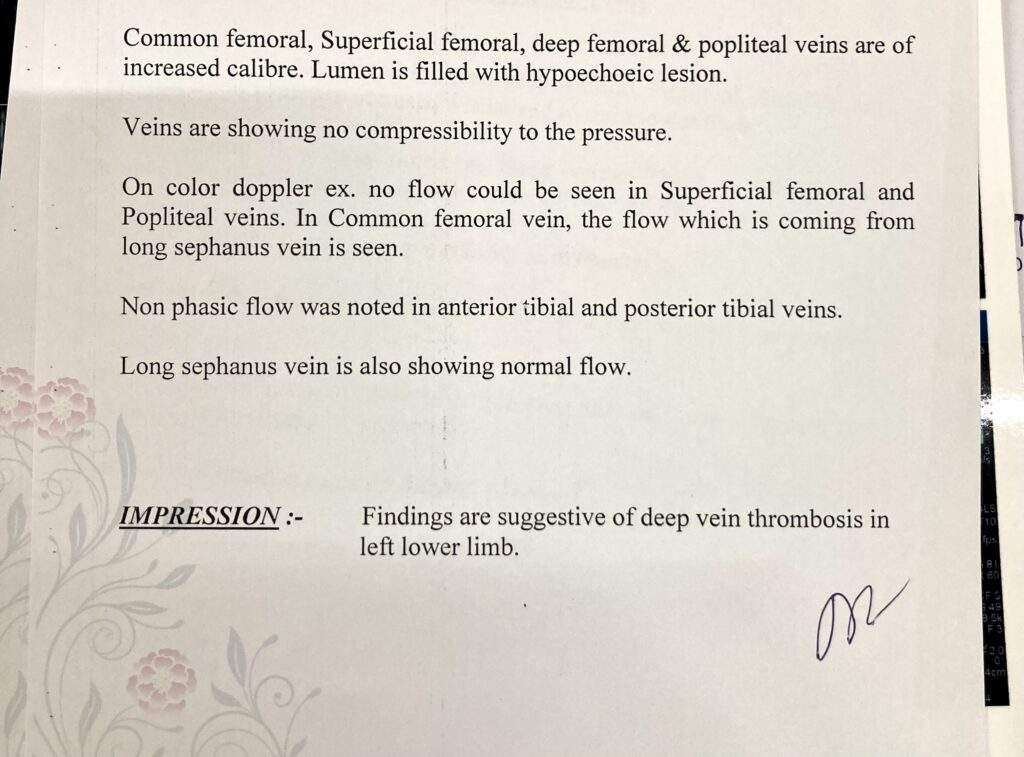

To diagnose DVT, your doctor will examine your legs to check for swelling and tenderness. He or she will ask about your symptoms and risk factors.

Based on the findings, your doctor may order a D-Dimer blood test or an ultrasound of your legs.

The blood test measures the level of a chemical called D-Dimer. It is almost always abnormally high when blood clots are actively forming in the body.

An ultrasound of your legs is done to look for blood flow problems in your veins. This procedure is called a lower extremity non-invasive test, or LENI. If the LENI shows evidence of a blood clot, your doctor will diagnose DVT.

If the initial LENI is negative, it does not mean that there is no clot. It may be too early to see the full effect of the clot. Your doctor may ask that you return in three to four days for a repeat LENI.

If your doctor suspects you have a pulmonary embolism, he or she will first try to determine if you have DVT. If the LENI shows one or more blood clots in your leg veins, and you have symptoms of a pulmonary embolism, an embolism is the most likely diagnosis.

Or your doctor may order computed tomography (CT) of the chest. The test requires an IV injection of dye to look for blood clots in the pulmonary arteries. People that have impaired kidney function or an allergy to the dye might need a different type of lung scan called a V/Q scan to examine lung blood flow.

Treating deep vein thrombosis

The initial treatment for a DVT or pulmonary embolism is heparin or one of the newer oral anti-coagulant drugs. These medications act on certain blood proteins to prevent new blood clot formation and therefore help unwanted clots get smaller. They are commonly called “blood thinners.”

There are two main types of heparin. The oldest type of heparin is best administered by a constant intravenous infusion. Another type of heparin is called low-molecular-weight heparin. It is injected under the skin once or twice per day.

Two of the newer anti-coagulant drugs are approved for initial treatment of DVT and pulmonary embolism: rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis).

If you have a DVT without a pulmonary embolism, you may not need to be hospitalized. You could be treated at home with injections of a low-molecular-weight heparin or either rivaroxaban or apixaban.

Some people may need to start therapy in the hospital. In this case, the type of heparin used is determined by many factors. These include body weight, kidney function and other circumstances.

If you have a pulmonary embolism, you will probably be hospitalized. If so, you likely will be treated with either type of heparin initially. But oral rivaroxaban or apixaban could be an option instead of heparin if your pulmonary embolism is small.

If you are started on either IV heparin or low-molecular weight heparin shots under the skin, your doctor will transition you to an oral drug. Traditional oral therapy has been warfarin (Coumadin). For decades, it was the only oral drug to treat DVT and pulmonary embolism.

In addition to rivaroxaban and apixaban, two other oral anti-coagulant drugs can be used after heparin: dabigatran (Pradaxa) and edoxapan (Savaysa). More of these types of drugs will be approved soon.

Warfarin takes a few days to start working. Once a blood test shows that warfarin is effective, you will stop taking heparin. You will continue taking warfarin for several months or longer.

During the first few weeks that you take warfarin, you will continue to need frequent blood tests to make sure you are taking the right amount. Once your blood test results consistently show that you are taking the right amount of medication, blood can be drawn every two to four weeks.

Some foods—especially green, leafy vegetables that contain large amounts of vitamin K—can alter the blood-thinning action of warfarin. Ask your doctor or pharmacist for a list of these foods. You can continue to eat these foods as long as you eat approximately the same amount of them each day. That way, the effect on your medication will be consistent.

Other medications can also affect how warfarin works in your body. Tell any doctor who is prescribing medications for you that you are taking warfarin.

The new novel oral anti-coagulants don’t require regular blood testing. They are given in a fixed dose. The other advantage is not worrying about eating food with too much vitamin K.