Contents

- 1 What is Sinusitis?

- 1.1 Different types of rhinosinusitis may be separated into the following categories based on consensus opinions :

- 1.2 Occurrence

- 1.3 Causes

- 1.4 How to assess the patient?

- 1.5 How to diagnose the condition?

- 1.6 How to manage the condition?

- 1.7 Symptomatic therapies

- 1.8 Be aware of potential complications

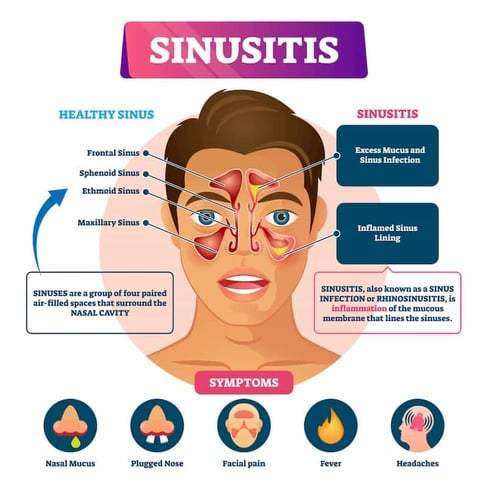

What is Sinusitis?

An infection of the sinuses is known as acute sinusitis. Rhinosinusitis is often a better word since the sinus passageways and nasal passages are connected. Acute rhinosinusitis is a frequent diagnosis, resulting in a significant amount of yearly healthcare costs and plenty of visits to primary care facilities. Additionally, it is a typical justification for prescribing antibiotics.

It can be brought on by bacterial, viral, or fungal infections, with viral infections being the most frequent. Antibiotics are frequently overprescribed in the treatment of this ailment, so it’s crucial to understand how to correctly examine a sinusitis patient and determine when antibiotics are necessary. In accordance with the recommendations made by several societies, this article covers the causes of rhinosinusitis and when antibiotic treatment in the management of this illness might be appropriate.

Different types of rhinosinusitis may be separated into the following categories based on consensus opinions :

- Acute – Signs and symptoms for fewer than four weeks.

- Subacute – It takes between four and twelve weeks for symptoms to subside.

- Chronic – Enduring symptoms for more than 12 weeks.

- Recurrent – Four episodes lasting fewer than four weeks, with full symptom relief between each episode.

Occurrence

One out of every five antibiotic prescriptions for adults is for acute rhinosinusitis, making it the sixth most prevalent cause for an antibiotic prescription. 6 to 7 per cent of children with respiratory symptoms are affected by acute rhinosinusitis.

Approximately,

- 16% of individuals are diagnosed yearly with ABRS. Given the clinical nature of this diagnosis, an overestimation is possible.

- An estimated 0.5 to 2.0% of viral rhinosinusitis (VRS) in adults.

- And 5 to 10% of children will progress to bacterial infections.

Causes

- The most prevalent cause of acute rhinosinusitis is viruses.

- The microorganisms responsible for viral rhinosinusitis (VRS) include rhinovirus, adenovirus, influenza virus, and parainfluenza virus.

- Streptococcus pneumonia (38%) is the most prevalent cause of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS), followed by Haemophilus influenzae (36%) and Moraxella catarrhalis (16%).

- Rarely, fungal infections may also cause acute rhinosinusitis, although this is virtually only seen in immunocompromised people.

- It is crucial to distinguish between acute invasive fungal sinusitis (IFS) and allergic fungal sinusitis (AFS), which manifests in immunocompetent people as a mass-like lesion filling a sinus canal and often causes persistent symptoms.

How to assess the patient?

1. Clinical evaluations often identify acute rhinosinusitis. The most sensitive and specific “cardinal” symptoms for acute rhinosinusitis are purulent nasal discharge accompanied by nasal obstruction or face pain/pressure/fullness. This must be determined particularly from people who report “headache” as a general complaint. Facial pressure is a symptom of sinusitis, but the headache is not (with the rare exception of sphenoid sinusitis, which may manifest as an occipital or vertex headache and is often persistent). The observant doctor must gather this information from the patient in order to ascertain the patient’s precise symptoms.

2. ABRS may be diagnosed if cardinal symptoms continue beyond ten days or if they intensify after an initial period of recovery (“double worsening”). Acute rhinosinusitis is accompanied by cough, weariness, hyposmia, anosmia, maxillary dental discomfort, and ear fullness or pressure. Mucopus coming from the osteomeatal complex may be detected by anterior rhinoscopy, or it may be proven by formal endoscopic rhinoscopy in the clinic.

3. The clinical manifestation of ABRS differs somewhat across children. Children are more likely to appear with fevers, in addition to the 10-day length, cardinal symptoms, and “double worsening.” Initial nasal discharge may be watery, then become purulent. Approximately 80% of acute bacterial sinusitis is preceded by an upper respiratory infection.

4. The severity of the symptoms suggests a bacterial origin. At the onset of the disease, these symptoms include high fevers (above 39 C or 102 F) accompanied by purulent nasal discharge or face discomfort for three to four consecutive days. Generally, viral diseases resolve within three to five days.

Antibiotic resistance issues must also be taken into account. These include:

- Antibiotic usage during the past month

- Hospitalisation within the preceding five days

- Healthcare profession

- Local antibiotic resistance trends are known to local healthcare providers

Finally, it is important to determine whether a patient is at increased risk. Included among these attributes are:

- Comorbidities (i.e., cardiac, renal, or hepatic disease)

- Immunocompromised states

- Age under 2 years or over 65 years

5. In immunocompromised patients, acute fungal rhinosinusitis is often accompanied by fevers, nasal blockage or bleeding, and face discomfort; however, it may also be asymptomatic. Refractory or severe symptoms should urge investigation of this diagnosis in immunocompromised patients.

How to diagnose the condition?

Clinical evaluations often identify acute rhinosinusitis. It is essential for the doctor to differentiate between VRS and ABRS in order to guarantee the appropriate use of antibiotics.

Local resistance patterns and prevalence of penicillin non-susceptible S. pneumoniae warrants clarification.

The conventional diagnostic criteria for adult rhinosinusitis include the presence of at least two significant symptoms or one major symptom plus two or more mild symptoms. In youngsters, the requirements are the same, with the exception of a greater focus on nasal discharge (rather than nasal obstruction).

Principal Symptoms :

- Purulent anterior nasal discharge

- Fever (for acute sinusitis only)

- Purulent or discoloured posterior nasal discharge

- Facial congestion or fullness

- Nasal congestion or obstruction

- Facial pain or pressure

- Hyposmia or anosmia

Mild features:

- Headache

- Ear pain or pressure or fullness

- Halitosis

- Dental pain

- Cough

- Fever (for subacute or chronic sinusitis)

- Fatigue

Here is some clinical advice for telling ABRS from VRS:

- Duration of symptoms exceeding 10 days.

- At the onset of the disease, a high temperature (above 39 C or 102 F) is accompanied by purulent nasal discharge or face discomfort for three to four consecutive days.

- Increase in symptom severity within the first 10 days.

In general, routine laboratory testing is unnecessary. Evaluations for cystic fibrosis, ciliary dysfunction, and immunodeficiency should be considered for chronic, recurring, or persistent rhinosinusitis. Some data suggest that a high ESR and CRP may indicate a bacterial infection.

The gold standard is the culture of endoscopic aspirates with more than or equal to 10 CFU/mL. However, this is not required for ABRS diagnosis and is not performed in the great majority of instances. Due to their weak connection with endoscopic aspirates, nasal and nasopharyngeal cultures are of little value. Referral for endoscopic aspiration may be beneficial for individuals with resistant infections or numerous antibiotic sensitivities.

Imaging is rarely indicated for acute sinusitis unless there is clinical concern for a complication or alternate diagnosis. Plain sinus films are often ineffective in identifying inflammation. They may display air-fluid levels. However, this does not aid in distinguishing between viral and bacterial etiologies. If a complication or other diagnosis is suspected, or if the patient has repeated acute infections, sinus CT imaging should be performed to evaluate for bone, soft tissue, dental, or other structural abnormalities, as well as chronic sinusitis.

These should be attained after an acceptable course of therapy. CT scans of the sinuses may reveal air-fluid levels, opacification, and inflammation. Over 5 mm of thicker sinus mucosa is symptomatic of inflammation. Additionally, it can efficiently evaluate bone deterioration or disintegration. However, these data are not useful for distinguishing between viral and bacterial etiologies.

MRI provides more information than sinus CT when evaluating soft tissue or illuminating a malignancy. Consequently, MRI may be useful for determining the severity of problems in situations involving ocular or cerebral extension.

How to manage the condition?

Antibiotic medication or a period of cautious waiting may be used to treat ABRS, provided that reliable follow-up is assured. There are minor differences in the guidelines of various expert committees.

The amended 2015 American Academy of Otolaryngology Adult Sinusitis guideline suggests amoxicillin with or without clavulanate for 5 to 10 days as first-line treatment for the majority of people. Failure of treatment is determined if symptoms do not improve or worsen within seven days.

The Infectious Disease Society of America Guidelines for Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis prescribe amoxicillin with clavulanate for 10 to 14 days in children and 5 to 7 days in adults as first-line treatment. Failure of treatment is determined if symptoms do not improve within 3 to 5 days or worsen within 48 to 72 hours.

the American Academy of Pediatrics Clinic Practice Guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 18 years recommended amoxicillin with or without clavulanate as first-line treatment. Uncertainty surrounds the length of therapy, although their recommendation was to continue treatment for a further seven days after symptoms disappear.

If, after 72 hours of therapy, symptoms do not improve or worsen, the treatment has failed. If the patient cannot accept oral fluids, ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg may be administered. If the patient can tolerate oral fluids the next day and improves, he or she may then begin an oral antibiotic regimen. To effectively address beta-lactamase-producing bacteria, a separate article recommends amoxicillin with clavulanate as the first treatment for children.

Adding clavulanate or prescribing high-dose amoxicillin (90mg/kg/day vs 45mg/kg/day) in children is determined by local antibiotic resistance trends, the patient’s risk level, risk factors for antibiotic resistance, and the severity of symptoms.

A third-generation cephalosporin with clindamycin (for enough coverage of non-susceptible S. pneumoniae) or doxycycline might be therapeutic options for penicillin-allergic individuals. The effectiveness of third-generation cephalosporins alone against S. pneumoniae is inconsistent. Fluoroquinolones might also be explored, although they have a greater incidence of adverse effects. In youngsters, doxycycline and fluoroquinolones should be administered with more care. S. pneumoniae and Hemophilus influenzae have elevated levels of resistance to second-generation cephalosporins, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and macrolides.

There is also evidence that antibiotic medication does not always reduce the duration of symptoms or the risk of complications in adults. Many instances of ABRS may also resolve spontaneously within two weeks.

Symptomatic therapies

Clinicians may give symptomatic therapies, but generally, there is a lack of conclusive data. In guidelines, nasal steroids and nasal saline irrigation are the most popular suggestions. By lowering mucosal oedema, intranasal steroids may assist in relieving the blockage. A limited number of clinical studies suggested that greater dosages of intranasal corticosteroids may reduce the period of symptom remission by two to three weeks. Additionally, nasal saline irrigation may aid in reducing blockage. Due to their ability to thicken nasal secretions, antihistamines are not recommended unless there is a definite allergic component.

Be aware of potential complications

Complications are uncommon, occurring in around one out of every thousand cases. Infections of the sinuses may extend to the orbit, bone, and cerebral cavities. 80% of orbitocranial problems manifest in the orbit. These problems may be associated with substantial morbidity and death. Due to the very thin ethmoid bone that divides infections from the ethmoid from the orbit, the orbit is the most likely location.

Prognosis

Most cases of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis are viral. The vast majority of cases are either self-limiting or efficiently treatable with antibiotics. In immunocompromised individuals, invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is an uncommon but severe type of illness. It is related to a high risk of morbidity and death.